Joining me on SPx is Professor Emeritus from Williams College, who actually still be teaching. So, mostly emeritus, but that’s a little bit of action to be had there. Charles B. Dew. Welcome, sir.

Thank you, glad to be here.

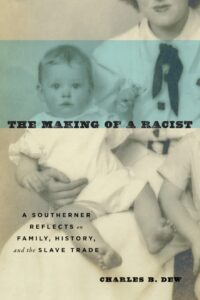

So, you’ve spent a lot of your life dealing with racism, and you had a personal transformation with it. And you’ve made that into, you know, a body of work for your life. And we’re going to dig into that a little bit today. Three books out, the one I just got through enjoying was, The Making of a Racist. And you know, what’s interesting for us, and for me was that you grew up here in St. Petersburg, Florida. And so, all of these things that you went through in this book were in places I recognize and attached to names that I recognize and people. Like the Gandy Bridge, and things like that all kind of play into this. So, as we dig into your experience of being made a racist, I think we should just start at the beginning, get some context and understand your upbringing.

Sure, St. Petersburg was a very southern town when I was born and grew up here. People have an illusion about Florida. That Florida somehow escaped the worst of what the South experienced. And that’s really not true. The segregation laws, the cradle to grave segregation. As I was growing up, the schools were totally segregated. Gibbs High was the African-American High School. There was a separate Black hospital – Mercy Hospital. What was then Mound Park Hospital, now the Bayfront medical complex was for Whites only. If you rode the municipal transit system, and you were African American, you move to the back of the bus. Housing was very rigidly segregated, there was the south side. And then there was Methodist town, which was above what was then 9th Street, which is now Martin Luther King. The town was basically as Southern as Macon, Georgia. And the races were segregated in almost every phase of life. I learned subsequently, that if you were an African American woman, and you wanted to buy a dress at one of the downtown department stores, they would sell you the dress, but they wouldn’t let you try it on before you bought it. And if you got home, and it wouldn’t fit, they wouldn’t let you bring it back. The African American population was not allowed to sit on the green benches. They were there for Whites, for retirees, basically. So, all of that was the environment in which I grew up and basically absorbed the values of that society.

And one of the points that you make, you know, a few times in your work is that the people in your inner circle, weren’t hateful, they had many wonderful qualities, good parents, good values on paper and in reality. And how interestingly that the situation expressed itself where, if you were a good person, the more loving and respectful way that you interacted with African American people, you actually felt good about yourself for having done that, even though in historical context it was pretty rough.

You were patronizing them, basically. One of the things that I found very interesting about people who have looked at the book, and when I’ve spoken in public, I’ve talked about this. And it always elicits conversation. How could good people have been complicit in this racist system? How did someone like my mother, Amy Meek Dew who was a lovely person, she had a kindness, a gentleness about her. She was a very devout Episcopalian. I grew up in St. Peter’s church over here, it’s now the Cathedral. I remember asking my mother once why the African American woman who worked for us – her name was Illinois Culver – why she lived on a far side of town and why we lived where we did, 25th Avenue North? And she said, “Charles, that’s just the way things are supposed to be. Illinois is happy on her side of town. We’re happy on our side of town. That’s just the way both folks are happy.” So that’s how it was justified in nice households, polite households. It’s just the way things were, and it was best for both races. My father was a lot blunter with his racism. He used racist language that my mother did not allow my brother and I to use. But he spent most of his early years here. He was actually born in Louisiana, but his family moved down here for health reasons. St. Petersburg was health Mecca, back in its early days. Suppose the climate, good for anything that ails you. And my grandfather had tuberculosis. So, two of my father’s older brothers, Roy and Joe Dew, came down here to scout St. Petersburg. They liked what they saw. And so, they paved the way for the family to come down. My uncle Roy – as I called him – later became the Cadillac dealer in St. Petersburg. Dew Motor Company was a household word in town. My Uncle Joe became the owner of Dew Furniture Company, which was another household name. As I said in the book, living in St. Petersburg, I never had to explain that my name was Dew and not Drew, because it was a name that was well enough recognized so that I didn’t have to do that. I think my father grew up in a more hardscrabble circumstance. His father died, not long after they got down here. And the boys had to go to work to support their mother, my grandmother. And there were three girls in the family, three boys in the family, boys went to work. And my father was 13 years old, sold newspapers to the trains that would come into the downtown stations, to the drummers as he called them. Salesmen who would arrive and get off the morning trains. So, it was a town in which I think they felt that they could thrive. Came here essentially, to look out for their father, and then settled in. My father, Jack Dew was the first member of his family to go to college. His two older brothers, put him through the University of Virginia as an undergraduate and then paid for his law school, also at the University of Virginia. And then he came back down here to practice law, met my mother when he was at the University of Virginia. And they married and arrived here in the mid-20s. And we made a life here. I was born in St. Anthony’s Hospital, grew up going to local schools, North Ward Elementary School was my primary school. Mirror Lake Junior High School, which I think is now a condominium, was my junior high school. When it came time to go to St. Pete High, which is where my father had gone to high school, this was the early 1950s. St. Petersburg had close to 100,000 people and we had one high school. And they were running two shifts in the St. Pete High. They were running a shift from 7:00 in the morning till noon, and an afternoon shift from noon to five o’clock. The schools that we now take for granted, didn’t exist, couldn’t get a bond issue fast. So, when it came time to go to high school, my father offered my older brother john, and I have the option of going away to an independent school, let us decide. We both decided to go away, went to an independent school in Virginia – Woodberry Forest School. So, I didn’t go to high school here, but came back and was certainly a part of this community and absorbed the values of this community.

And following along on those values, there was such an energy that drove the racism that seems to almost supersede any sort of immediately accessible consequences or bad things that may happen. And you actually pinpointed one of the real drivers to that. If you look back historically, greed is certainly a big part of it, right? It was the cotton industry you equated to the oil industry, and then just the money is there. But as we moved out of that, that financial incentive or that financial structure, or drive wasn’t as prevalent, but yet the passion behind the racism was still there. You mentioned that you never heard your father really lose his temper in any way like the day that, one of the shoeshine folks came and went just to the side door instead of the back door. And he lost it, right? And there’s a lot of energy behind that.

Yeah. That was one of the most traumatic experiences of my childhood. And I learned again, when I had been out speaking in public about the book, every person who grew up in that culture, either White or Black, had a searing moment that occurred in their childhood that taught them the importance of race. If you are on the African-American side of the color line, it was a searing experience that was never forgotten. If you were on the White side, it was also something you never forgot, but it wasn’t the powerful element that Black individuals experienced. The incident that occurred – as you’re referring to – happened when I was eight years old. We lived at 234, 25th Avenue North. And there was a driveway in a park a share where my father kept his car. We had just started using the car again. Rationing was on during World War I. You didn’t drive the car, because gas was rationed, rubber for tires was rationed. You just took the bus. And the war was over. And we had started using the car. And my father and I would get in the car, and he would drop me at North Ward School, which was right on 4th Street, as he would go on to his office. On the morning that you’re referencing, a man named Bill Williams. I didn’t know his last name then. We didn’t tend to know the last names of African American people, even if they worked for us. It was first name only. All I knew was that his name was Bill and he owned a shoeshine parlor, in an arcade downtown where my father got his Spectator shoes shined. And quite clearly, my father had been in there the day before, and something had happened. One of the shoeshine boys, they were called, they were all grown men. I think probably had said something my father had overheard, but my father stormed off in anger. And clearly had either told Bill that he wasn’t coming back, or Bill perceived that. Bill Williams was coming to our house to apologize to my father. And I saw him coming down the sidewalk. And then I saw him cut into our yard. And he approached us, as we were exiting the side door from our living room to the [11:16]. And as my father saw Bill approaching the house, he exploded in rage, cursing Bill, screaming at him. I had never heard him, yell and scream at anybody. I was terrified. I don’t remember exactly what he said. But I realized what had happened. Bill had broken one of the cardinal rules of Jim Crow Etiquette. He had approached our house, from the wrong door. Instead of coming to the back door, which is the only door African-Americans were allowed to use. He had approached our door from the side. It was a side door, and that just… It was a volcanic eruption on my father’s part. And that impressed on me, an eight-year-old. This is something powerful. And I was learning. I was absorbing this elaborate racial etiquette. It’s kind of an awkward etiquette that governs the relationship between people of different races. But that’s exactly what it was. And a lot of that etiquette, a lot of that attitude, a lot of that belief system, I didn’t have to be told. I just absorbed it. I use the word osmosis in the book. I watched the way my parents behave toward people of color. I watched the way my aunts and uncles, people I loved and respected behave. And I learned, this is the way White folks act around Black folks. There were very, very few things you could actually talk about across the color line. You could talk about the weather, you could talk about baseball, as long as you didn’t mention Jackie Robinson, or one of the African American players who was integrating. You could talk about cars. There were some things you could talk about. But you could never even get remotely close to segregation, to social justice, to any things like that. It wouldn’t have occurred to most Whites to even bring something like that up. And if a Black person was engaged in the conversation, and that did come up, they would retreat very quickly, because this was dangerous territory. You didn’t get into a conversation with a White person about social justice. You tipped your hat, you said, “Yes, ma’am,” and, “Yes, sir.” And you went about your business. So really, there was no way for me to learn another way of life. The power of that Jim Crow culture was phenomenally strong. And there really wasn’t any way to break free of it. I think and remain in that culture, remain in the south. I said I went away to high school. It was the same thing in Virginia I’d experienced here. So, I didn’t begin to get educated until I went north to college.

And, you use the term volcano, which I think is apt. Because it implies, a lot of pressure lying under the surface. And it seems that this etiquette structure that existed, was sort of there to protect against eruptions. And one of the big things that, you know, going back to the what’s driving this pressure. And a lot of it was the fear of sex, of interbreeding.

Absolutely.

And you know, at the end of the day, that’s the idea. You know, the racism expressed itself as a fear of Black men having babies with White women and sort of differently, going the other way, Black women corrupting White boys – Black girls.

Exactly. And that I think, realized is something that I didn’t know at the time. I was absorbing, and that’s the power of stereotypes. Black men were stereotyped as potentially dangerous, too easily lured into violence, hyper sexualized, lusting after White women. Black women were stereotyped as Jezebels, as loose women, as people who would compromise White males, in order to get something from them. I’ve often referred to this, when I’ve been teaching courses in southern history. I don’t think anything illustrates the power of stereotypes, any more than a simple fact. In South Carolina up until 1895 – and I would ask my classes this. Up to 1895, the age of consent for girls was what, when they could consent to sex, and it wouldn’t be statutory rape? And I’d get, “Oh, at 16, 14, 12.” No, it was 10, 10 years old. And that’s because of that Jezebel stereotype. At the age of 10, a Black woman would lure a White boy to her bed to get ahead. And that fear of the sexual violation of the color line was at the heart of the Jim Crow system. And this had been a belief system that was in the south for decades, and generations. And that fear and the racism that accompanied it, was passed down from generation to generation among White Southerners, almost like a genetic trait. And it was incredibly difficult to see anything else as the proper way that the races should interact with each other. Segregation, cradle to grave, with the Whites on top, and the Blacks on the bottom. In my scholarship, as a historian, I got involved in writing a book on the secession crisis. Came about in a rather odd way. I was doing research on something quite different, and was looking at newspapers just before the Civil War, looking for one subject. Found a report of a speech that a southern – a secessionist, had given to the Georgia legislature, before Georgia seceded from the union. And for some reason I started reading down it. And I found the same language in that 1860 speech that I had heard growing up in the south, in St. Petersburg, Florida, in the 1940s, and 50s. All those stereotypes were there. The sexual threat that Black males pose to White women. And if Lincoln were allowed to take office in the south, deep south, the slave south didn’t move to protect itself, we were facing Armageddon. We were going to lose our property, which was worth billions of dollars in 1860 money. We were going to face a race war, because the freed slaves would come after us, just as it happened in Haiti. And the Black men would come after our women. And the same thing was being said, to promote secession in 1860-61 that I was being raised on in Florida, in the 1940s, and 50s. And I made a mental note. I was doing another project, to come back to this and just check this out. And it resulted in a book I wrote on the secession crisis. So, there’s a long life to this stuff. And it really manifested itself to me as I was growing up. And as I grew into adulthood, I became convinced that this is what I wanted to try to come to grips with and understand. And that’s why – unlike everybody else in my family who became lawyers – I decided to go to graduate school and study history.

But it’s such an important observation, that fear element. And obviously, people stereotype everything. And there are other racism that have stereotypes that aren’t as laden with fear. But that fear was so powerful that, it was pointed at African-Americans, but it didn’t stop at African-Americans. Because the fear was so powerful that, you at times didn’t stand up to people in some of the fraternities who were saying things that you disagreed with. But the risk to you even saying something as a White person was there. You had an uncle who was a pediatrician. Who was one of the few people who saw both Black and White patients, but still joined this white-collar guild, which essentially you called a white-collar KKK.

White Citizens’ Council.

White Citizens’ Council, right? And he did so, because he feared for his White children. So, you know, the fear and the racism that came out of it, didn’t even stop at just African-Americans. It was so powerful.

Absolutely. And the incident you’re referring to was in the civil rights era. Yeah, the White Citizens’ Council was founded in Mississippi. And it was sort of white-collar clan. In the sense that, they didn’t advocate violence. But they advocated every means short of violence to oppose the Brown decision in 1954 that integrated the public schools. And the Citizens’ Council spread across the south. And were one of the bastions of resistance to school integration. And they involved the business community, the professional community and White cities, small towns. And the town my pediatrician uncle lived in Orangeburg, South Carolina. It turned out was one of the places that was particularly a White Citizens’ Council bastion. Then I was in college. I was going to college in Massachusetts. I had begun to pull back from my belief system that I had grown up with here. I would stop on my way, driving back to college in western Connecticut at his home in Orangeburg. And I remember him telling me that he had joined the White Citizens’ Council to protect his children from being harassed. And by that time, I had come to a sort of parting of the ways with my Jim Crow culture. It happens slowly, incrementally. I’m appalled. Looking back on it, how slowly it did come to me that I was complicit in a horrific system that humiliated people on a daily basis, on the basis of the color of their skin. But during my four years at a New England liberal arts college, I really became a different person, I would have to say. That my father would send me there, there’s a story there. If you’d like me to tell it.

Mr. Gandhi’s, I’d love to hear that, yeah.

This is Mr. Gandhi. Av Gandhi was one of my father’s clients, and he wanted to build a toll bridge across Tampa Bay. And he sent my father to New York to talk to investment bankers, bond attorneys. The kind of people who would provide the capital to build that bridge. And my father, because of his experience, going to the University of Virginia believed deeply in the value of education. And his measure of an educated person was how well they use the language. If they wrote well and spoke well, and he interacted with them. He would say, “By the way, where did you go to college?” My brother and I, he wanted us to be well educated. And a disproportionate number of the men he ran into said, “Williams College.” And my father had no idea where that was. “Where is that?” They told him it’s a small men’s college, liberal arts college in western Massachusetts, great teaching college. And he had a friend down here who had gone to Bowden. A man named George Houston ran a real estate office in St. Pete, good friend of my father’s. George Houston was from Bowden. He knew all those New England [inaudible], “Oh, yeah, Williams that’s a wonderful college. Great place. You should look at that for your older boy John, and your younger boy, Charles.” So, he did. My brother and I completed our independent school in Virginia, was an all-boys school out in the country. A monastic life for high school males. My brother had his heart set on going to the University of Virginia and majoring in fraternity life. I say that facetiously, but only halfway. My father said, “No, you’re going to go to Williams College for a year. If you don’t like it, you can transfer.” Well, my brother loved it. He came home, talked about his professors, talked about how much he loved the school, the friends had made there. So, I just paddled along to Williams in the wake of my brother. And plunking me down in a New England college campus was transformative. It changed my life.

And it’s so interesting, it really speaks to the absolutes surety that your dad had. You know, he came to you and said, “I want you to go out in adventure and be independent and soar and find yourself.” Yet, you have to suspect that had he known that you would have changed these specific views, he might have reconsidered sending you. But that’s how absolute it was, that he could feel confident that he was being adventurous to sending you there and assume that that would never change.

That’s exactly what I came to conclude. And my father and I had a parting of the ways by my senior year, which I’ll be glad to talk about if you want. But you’re very astute in mentioning that. I think he thought the segregationist armor in which we were clad, was impenetrable. That we had absorbed what he called the basics. And if you were a southern White male, the basics meant that you held the color line. If you were a man, you were a boy, you were expected to man the ramparts of Jim Crow. And to see to it that those Black boys and those little White girls never ended up in class together. Because we knew the Whites said, if that ever happened, what the consequences would be. So as a White Southern male, you were raised with the notion that you are guardians of a tradition. And you waver from that, and you compromise that only at great cost, your acceptance in White society, your respect your standing. There was a label that was thrown out at people who made that kind of move, and who expressed those kinds of sentiments. It was the N word, coupled with the second word lover. And that’s what you would find yourself immediately called if you raised any sort of doubt at all about segregation and that system that was in place. So, it was incredibly powerful. It had a coercive power that’s almost impossible to define. And of course, the thing about growing up in a privileged world, if you’re White in this world you think that’s the world. That’s the way things were meant to be. That’s the natural order of things. So, only when you get some distance I had African-American classmates at Williams. I had never been in a position where I was on the same level with a person of color. Yeah, I think my father was really convinced that didn’t matter. We’d get educated. We’d learn to speak well and write well.

I would assume that goes back to – something that’s that absolute has to again go back to that fear. It’s self-preservation, and if you believe evolutionarily if, you know, the downside to something, you know, eating a berry. The downside of that could be dying and the upside is eating a berry. So, where sort of fear is a very strong driver, indeed. And there’s fear of the unknown. Then coupled with that, which is where, the power of keeping that fear alive through segregation really comes into play. And you know, what your life experience was is, that veil gets pierced when you’re in a place with other humans, regardless of their color and start to identify with them as they’re human. So, I think your journey encapsulates, an instructive way to connect and to dissipate the fear.

I think that’s absolutely correct. And I’ve always thought, as I was looking back on how I grew up and getting away from this culture. If I had stayed here, that would not have happened. Because of the power of the culture, and the fact that everything you encounter reinforces it. There are no permissible breaks. There are no questions that can be asked. It’s the way things are ordered and meant to be and will always be. I think that if I hadn’t been in college where I was, I probably wouldn’t have had the… I know this, I would never have had the interest in asking the African-American woman who worked for us about her life. And I did that. And that was really, I think, one of the critical moments in my emergence from the way I had been brought up. I’ll be glad to talk about that.

Yes. And this is when you drove her home every day after, was important.

Her name was Illinois Browning Culver. She worked for my family for as long as I can remember. She cleaned the house, she did the laundry, she occasionally cooked dinner for us. No air conditioning back in those days. It was hot in the kitchen. If, at the end of the day, my mother decided that Illinois was there and could be asked and agreed to fry up some chicken or prepare a meal for us, she would do it. And as I went to college and began to question my Jim Crow heritage, I really wanted to talk to her. And when I got my driver’s license, I would volunteer to drive her home. She lived over on the south side. Because I was hoping that I could learn something from her about her life. I was a junior in college by then. And I remember the day as vividly as was yesterday. She sat in the front seat, there was a protocol that the maid or whomever you were taking home was supposed to sit in the backseat. We didn’t do that. I don’t know how that developed, but it did. She sat in the passenger seat and I was driving. And I thought I would break the ice by asking her about her son. I knew they had a boy Roosevelt, and he had left St. Petersburg as soon as he was old enough to do so. I think he’d gone to California gotten a good job with an airline as I recall. And I wanted to find out about her life. And I said, “Illinois, you know, it’s a shame that your son Roosevelt had to leave St. Petersburg because of something like race.” And she looked over at me and I remember how quiet she was. It seemed like for a long time, this was dangerous territory for her. If she was going to break that rule and start talking to me about social justice, about bigotry, about race prejudice. She didn’t know what the consequences would be for her. But I think she knew me well enough to trust me. And she said, “Yes, Charles, it is a shame Roosevelt had to leave because of something like race.” And that opened up a whole world for me. The way she had been forced to live her life simply because of the color of her skin. I realized as I was writing about this, it had a sort of, I don’t know, like Grade B Hollywood twist to it. Well-meaning White folks being educated. I was thinking of the movie, The Help, but it happened. And I thought, “Okay, it’s very important that this be told.” And that’s where I really learned about the humiliation that was visited on her. The business about buying a dress came from her. The business about the green benches came from her. I remember she would clean the house for us. And when she got to the living room, we had one television they were huge big boxes. They were very expensive. If you had a TV in the 1950s, you had one and it sat in the living room. And she would ask my mother if she could turn the television on while she dusted the living room. And my mother said, “Sure, that’s fine Illinois.” She would always time it so that she could watch a quiz show called, The Price is Right. Bill Cullen was the host. And I remember saying one day, “Illinois it’s fascinating that you time your visits to the living room when The Price is Right is on, Bill Cullen. You must like that show and you must like Bill Cullen.” She said, “I like Bill Cullen. I like that show. You know, Charles, that’s the only quiz show that has Black folks on as guests.” I had never been remotely aware of that. She of course, had been acutely aware of that, because it didn’t exist anywhere else. So, this is the one place where she could watch a national television program. And get something remotely like an affirmation of her worth. And I remember just being appalled by that. I had never had an inkling of that. But she had it – as I say – visited on her daily. And I realized that this was abominable. And it had to change. And that’s when my attitudes became, I think, really changed for good. And one thing she told me is really at the core of the book I wrote, I forget the exact context of the conversation, I think I was asking her about some of these crazy, Jim Crow customs, I’ll just cite one. As I say, Illinois cook dinner for us regularly. But I remember as a boy growing up that there was some China in a cupboard in our kitchen, some orange China, that was distinct. We didn’t have any other plates, saucers or cups, anything like that. And I remember being told that that was the China on which Illinois and Ed – the man who mowed our grass, I never learned his last name. They were to eat their lunch on those plates. There were a couple of jelly glasses there. They were to eat on those plates. And we were to eat on these plates. And we were never to use those plates and Illinois and Ed were never to use our plates. I was taught that when I was knee high. And I started thinking, “Why should Illinois cook our dinner, and be forced to eat on essentially segregate plates?” I think I was asking her about something like that. And how did that come into being? Where did that come from? And she looked over at me and I think she was almost in tears. And she said, “Charles, why do the grownups put so much hate in the children? Why do grownups put so much hate in the children?” As soon as she said that, I realized she had nailed it. Those customs, those attitudes, that bigotry was passed on to me, father to son, mother to daughter, just like as I said earlier, a genetic trait. And one generation of White Southerners pass that on to the next and it got transmitted, never questioned. And it became the equivalent of scripture. This was gospel. And realizing that she had put into words, the process by which this bigotry was passed on was something I never forgot. And when I sat down to write about this, I realized how important that was, and really used that as one of the central themes that I tried to develop as I wrote the book. I am beholden to her. The book is dedicated to her memory, Illinois Browning Culver. And I am just eternally grateful for the fact that she trusted me and was willing to talk.

And after that, I’d like to dig a little bit into when you talk about your attitude changing. I think that is true, and it’s a bit passive compared to the actions you have taken. You mentioned another story where the thread of humor that you had growing up was sort of talking in an African American dialect. And it was part of many of the jokes. And when you were first at Williams, an African-American boy that you ended up becoming good friends with overheard you, and you stopped dead in your tracks, and you were mortified by it. And that’s one of those times where you said you never made a joke using the dialect again. That’s the standard example of – to me – attitudes changing, but you took it a lot further than that. You’re writing books about it. You made a career out of it. How you stood up your dad for it. So, can you talk about how these realizations inspired you to take the steps that you took?

Sure, I had great teachers in college, and I had one professor, particularly who sort of took me under his wing. And he taught American history. He taught the history of the South. And I took a course from him my junior year, which really began the sort of educational transformation as opposed to the cultural transformation I had undergone. I was learning Southern history that had nothing to do with the myths that I had grown up with as a White boy, growing up in the Jim Crow South. Just to give you one example, back in my day, 14 was the age at which you passed from boyhood to adulthood. And at age 14, you were given generally a firearm – 22 caliber rifle, which you were supposed to learn how to use because Southern boys knew how to shoot, how to hunt. And you were also often given something that had to do with the Confederacy. And in my case, my father gave me a famous history of Robert E. Lee’s Army, Douglas Southhall Freeman’s Lee’s lieutenants, which was a three-volume history of the army of Northern Virginia. And I just devoured that as a boy took my 22 out, and when I was plunking at cans I was looking at Blue coated Yankees at Gettysburg. So, my whole experience growing up in the south was Basically absorbing the myths about the civil war being about states’ rights, about Lincoln and the abolitionists being a threat to the south, and to our slaves who we took good care of, looked after families. They weren’t overlooked. They were worth a lot of money, and so they were cared for. So, the version of Southern history I absorbed was so myth-encrusted, that it bore no semblance to reality. And as I went through the history major at college and got to the first semester of my junior year, I took a seminar with Professor Bob Scott, on the History the Old South. And that did for me, educationally, what my experience in a New England college with African-American classmates had done for me culturally. And I decided, unlike every other person in my family, I was not going to go to law school. I wanted to go to graduate school, I wanted to study Southern history, I wanted to try and get my head and my hands around this place and this culture. So that’s essentially what I did. The professor whose book I read, that was probably the most meaningful book, I read that junior year was a professor at Johns Hopkins named C. Vann Woodward. That’s who I wanted to work with. So, I applied, got in and that’s where I ended up. So, I’ve spent both my actual life and my scholarly teaching life, trying to understand the place where I was born and raised; its values, its culture, how these developed historically, the burden that they have placed on the region, and its people. So, as I move from a teenage boy, with my 22, and my history of Lee’s army, to college and then to grad school, I simply tried to acquire the kinds of tools I would need to examine the south and southern history critically and historically. And that’s what I’ve spent my life doing both as a teacher and as a scholar. And the making of a racist was a book that I wrote late in this career, I’m talking about. And one of the reasons I wrote it was that I frequently would talk about my experience growing up in the Jim Crow’s South as illustrative of things that I was teaching about the Old South, about the 19th century, even the 18th century. And I noticed when I was talking about my experiences, my students stopped looking out the window and focused on me, because I was telling him about my own life. Often, several would come by my office to probe this bizarre culture that I was describing. And when it came time to decide, as I was getting to the point that I wrote this book, what I was going to write about next. I decided I would try to unravel my own history. And that’s the first half of the book. Second half is on a document concerning the slave trade that really was a moment of self-examination that occurred to me, that made me realize that I had been as complicit in the Jim Crow system, as my antebellum White Southern ancestors had been complicit into the slave system. And I saw that complicity as joining us at the hip. Yeah, segregation wasn’t slavery. But it was the post emancipation 19th/20th century version of bondage. Human beings weren’t property as they had been under the enslaving system that existed in the Old South. But in so many other ways, the predecessor was being acted out in the successor, the Jim Crow successor. So, I put the book together, I took a document that was very important in making me realize how these two systems were joined, and wrote it up, sent it to my publisher said, “I don’t know if there’s a book or not.” And they said, “Well, we’ll publish it.” So, they did.

Worked out. So, when you had those realizations and what I was getting at, and just all the problems with the word and the label aside the general intention that, at any point then, would you consider yourself an activist?

An activist. I have been an activist, as a teacher and a scholar. There really wasn’t any Jim Crow to fight where I ended up. I ended up back at Williams College to teach most of our life there. Had thoroughly integrated classes, thoroughly integrated faculty, thoroughly integrated staff. And what I tried to do as a reformed Southern racist, was to teach to the best of my ability, every generation of students who went through my classes, what had gone on. So that they would be aware of this and they would be a force to prevent something from like this ever happening again. That they would know racism when they saw it, no matter how disguised it was. No matter if it was done with a dog whistle or a bullhorn, they would know it, and would be able to say, “Wait a minute, hold on, we’re not going back there.” Unfortunately, I think we are still facing these problems. One of the great scholars of African American History and Culture, WB Dubois wrote a book published 1905 called, The Souls of Black Folk. And in it, he said, the color line, this is 1905. The color line is going to be the problem of the 20th century. Well, here we are in the 21st century, anybody want to tell me the color line isn’t still a problem. I don’t think you’d get very far with that. So, we’re really living with the consequences of human bondage, of the coercive system that was put in place to segregate the races after emancipation, that existed deep into the 20th century, it really didn’t begin to get challenged friendly until the Civil Rights Movement 1950s. We didn’t pass legislation, Civil Rights Act till 1964. We didn’t pass the Voting Rights Act till 1965. We didn’t pass the Equal Housing Act till 1968. It took Martin Luther King’s assassination, to get that bill through Congress. We’re still living with this. So, I think in answer to your question about activism, I think my teaching and my scholarship probably represents my activism. And I have been speaking a lot following the wake of the publication of the book. In the post Obama era, we are experiencing some blowback to the first African-American president. So, I think what I’ve written about and talked about and taught is still very much relevant. And so, I’m talking to you now. I’ll be giving some talks at other places, other venues. I’m delighted to do this. I don’t have a speaker’s fee. I say, “Send me a train ticket I’ll come.” I still like to ride trains. It’s how I grew up. Because I think if any community, anybody wants to have me talk about what I experienced and what we can learn from it. I want to do that. So yeah, I haven’t been an activist in the sense of a street warrior. I think I’ve been an activist in terms of my teaching and what I’ve tried to study and write about.

Wonderful, and we appreciate that writing and that teaching, and your time today. Thank you, Charles Dew.

Thank you enjoyed this very much.